In late January 1949, a brief typewritten letter travelled from Bombay to New Delhi, addressed simply to the Secretary of the India Constituent Assembly. The letter came from a organisation now largely forgotten – the Bombay Civil Liberties Union (BCLU).The accompanying resolution enclosed nine proposed fundamental rights that broadly mirrored those in the Draft Constitution 1948. Yet, the BCLU’s submission contained a forceful plea

“The Conference regrets that the present draft Constitution, including the part so far adopted, does not guarantee these Fundamental Rights but has virtually rendered them nugatory by various restrictive qualifications and provisions regarding emergency measures, and so the Conference urges that anything in the draft Constitution repugnant to or inconsistent with the enjoyment of these Fundamental Rights by the citizens should be deleted.”

The Union’s statement captured a sentiment shared by several members of the Assembly—deep unease restrictions attached to the fundamental rights provisions. Clearly, the BCLU was unconvinced by B. R. Ambedkar’s defence of these limitations, which many feared would hollow out the rights themselves.

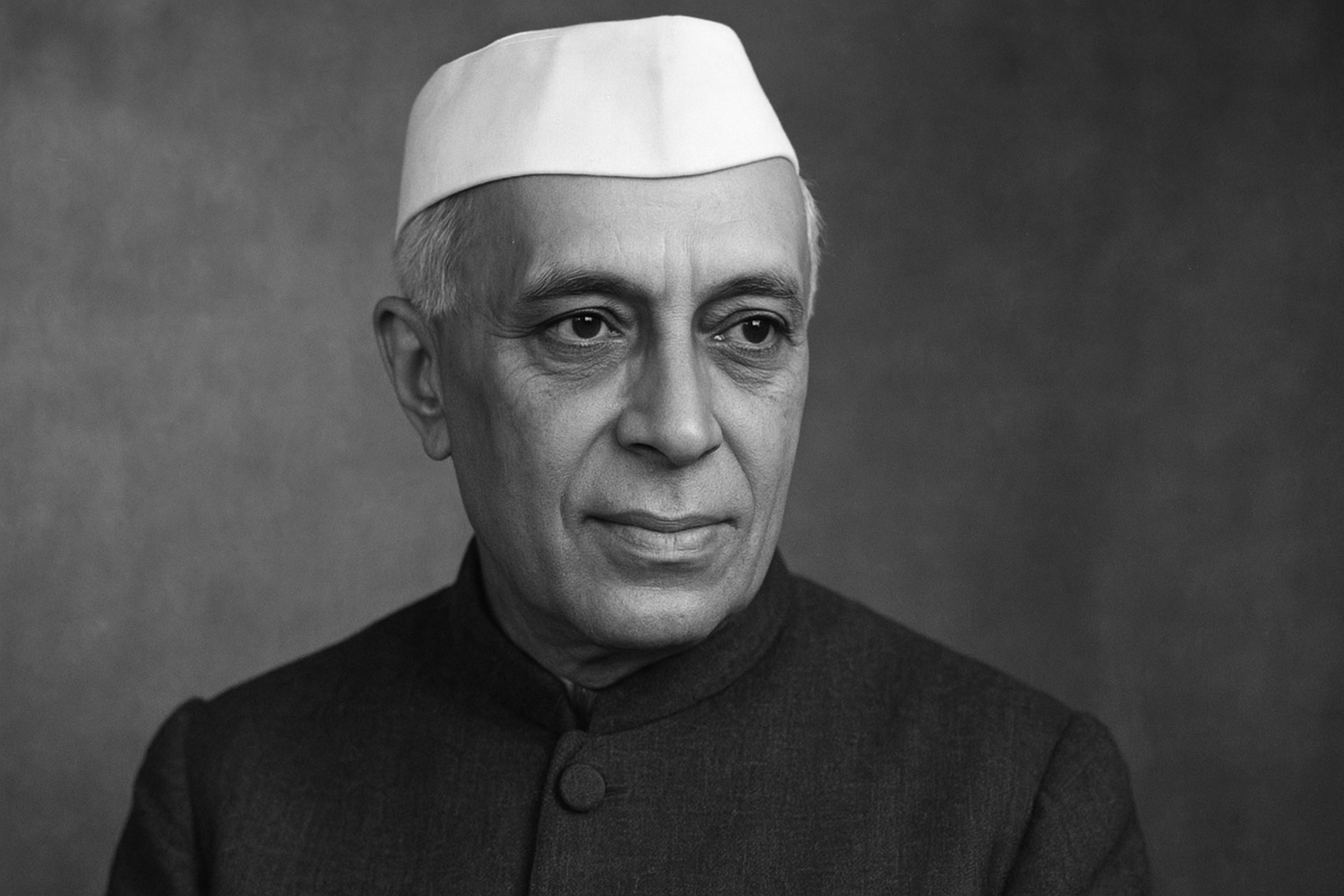

The Bombay Civil Liberties Union had been established more than a decade earlier as the Bombay branch of the Indian Civil Liberties Union (ICLU), both inaugurated on 24 August 1936 at the Blavatsky Lodge Hall in Bombay. The ICLU was conceived by Jawaharlal Nehru after his interactions with the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) in the United States and the National Council for Civil Liberties (NCCL) in Britain. These encounters convinced him of the need for “a joint effort embracing all groups and individuals who believed in civil liberties” within India.

Nehru envisioned the ICLU as a broad-based, cross-party organisation that would bring together professionals, political leaders, and public intellectuals committed to protecting basic freedoms. He sent letters of invitation to 150 eminent Indians, but the responses were mixed. Some declined in pointed terms—one correspondent remarked that Nehru’s “intolerance of views” in his autobiography made cooperation impossible.[i] Even liberal figures such as Tej Bahadur Sapru were skeptical, suggesting that reforming repressive laws would be better achieved through changes in political practice rather than through a new organisation.[ii]

Despite this resistance, Nehru succeeded in assembling a distinguished group. Rabindranath Tagore agreed to serve as honorary president, Sarojini Naidu became the working president, and Bombay was chosen as the headquarters of the new movement. As a local committee of the ICLU, the Bombay Civil Liberties Union adopted a clear set of functions. Its provisional constitution outlined its primary activities: collecting information about the suppression of civil liberties, publishing statements and reports to inform the public, organising protests and vigilance groups, providing legal and other assistance to victims, and maintaining communication with the central office in Bombay.[iii]

The BCLU endorsed the aims laid out in Clause 2 of the ICLU’s Provisional Constitution, upholding the principle that “all thought on matters of public concern should be freely expressed without interference.” It viewed the freedoms of speech, thought, expression, press, and assembly as essential to orderly social progress. The Union sought to defend these freedoms from encroachment by executive or judicial authorities—especially through ordinances, emergency powers, or preventive detention laws. To this end, it pledged to investigate violations, publish findings, organise public protests, and provide legal aid to affected individuals.[iv]

Correspondence from K. F. Nariman, the BCLU’s joint secretary, offers glimpses of its early functioning. In one letter to M. R. Jayakar, Nariman described the formation of a three-member committee to inquire into alleged judicial misconduct by the Resident Magistrate of Kalyan and invited Jayakar to serve as chair. Such initiatives reflected the Union’s attempt to make the defence of civil liberties a matter of organised public concern rather than sporadic outrage.[v]

Despite these early efforts, the BCLU’s influence waned rapidly. After Independence, Nehru reversed his earlier position, arguing that a separate organisation to monitor civil-liberties violations was no longer necessary. He withdrew his support from the ICLU and recommended its dissolution—a decision made easier by the fact that the body was already moribund. This reversal was not entirely surprising. The Indian National Congress itself had long been the principal advocate for civil liberties, both through its political campaigns and through documents such as the Karachi Resolution of 1931 and the Nehru Report of 1928, which had articulated robust civil-rights guarantees.

Yet, as historian Arudra Burra has observed, the civil libertarian impulse nurtured by the ICLU and BCLU did not vanish entirely. Figures associated with the Bombay branch—such as Romesh Thapar and trade unionists like Dinkar Desai—later became prominent in the post-Independence civil-liberties movement. Burra suggests that threads of continuity may be traced from the BCLU’s work to the rights-based advocacy that surfaced in early constitutional cases such as V. G. Row v. State of Madras (1952) and A. K. Gopalan v. State of Madras (1950).

…………………………………………………………………………

[i] Indian Culture, Indian Civil Liberties – Papers, press cuttings and correspondence re. the formation of Indian Civil Liberties Union, Collections – Digitized Private Papers, M. R. Jayakar, https://indianculture.gov.in/archives/indian-civil-liberties-i-papers-press-cuttings-correspondence-re-formation-indian-civil-0, p 19.

[ii] ibid p 26.

[iii] ibid p 14.

[iv] ibid p 23.

[v] Ibid p 27.