The winter session of Parliament witnessed heated controversy over “Vande Mataram” during its 150th anniversary—a song inextricably linked to India’s nationalist movement. The debate erupted when the ruling government accused the opposition of removing portions of the song during the parliamentary program, while the opposition defended its approach by citing the song’s historical connection to their party’s own decisions. This contemporary dispute echoes unresolved tensions from India’s founding moment, making it essential to examine two critical episodes when the political leadership first grappled with “Vande Mataram”: the 1937 Congress Working Committee resolution and the Constituent Assembly debates.

The 1937 Congress Working Committee Resolution

The controversy over “Bande Mataram” (as it was also spelled and pronounced) had been building through 1937, prompting internal discussion among Congress leaders. In a revealing letter to Subhas Chandra Bose, Jawaharlal Nehru outlined his approach to the issue. Nehru was reading an English translation of Anandamath to understand the song’s background and acknowledged that “this background is likely to irritate the Muslims.” He recognized the language barrier—most people could not understand Bengali without a dictionary—and noted that while “the present outcry against Bande Mataram is to a large extent a manufactured one by the communalists,” there appeared to be “some substance in it.” Nehru was clear about his principle: “Whatever we do cannot be to pander to communalists’ feelings but to meet real grievances where they exist.” He planned to discuss the matter with Rabindranath Tagore to clarify the Working Committee’s position.

This deliberation led to the Congress Working Committee’s carefully calibrated resolution in December 1937. The Committee acknowledged the song’s origin in Bankim Chandra Chatterji’s novel Anandamath, clarifying that it had been composed earlier and only later incorporated into the novel. They traced the song’s political evolution, noting how British colonial authorities deemed it seditious and violently suppressed its use, while generations of freedom fighters embraced it as a symbol of resistance and sacrifice.

The resolution made a crucial distinction: the first two stanzas, which praised the motherland’s beauty and abundance, had gained national acceptance over decades without causing offense to any community. These verses celebrated India as a nation accessible to all its people. However, the Committee acknowledged concerns raised by Muslim colleagues regarding the later stanzas, which contained religious imagery. Their recommendation was clear—restrict national use to the first two stanzas only.

Importantly, the Committee specified that “Vande Mataram” had never been formally adopted as the national anthem but held a unique and cherished place in national life. They appointed a sub-committee including Maulana Azad, Nehru, and Subhas Chandra Bose to evaluate national songs for official recognition, demonstrating their commitment to developing an inclusive musical tradition for India’s diverse population.

This resolution reveals the Congress leadership’s attempt to balance the song’s historical and emotional significance with communal sensitivities, establishing a precedent for how independent India might navigate questions of national symbols in a plural society. Nehru’s private correspondence shows this was no simple calculation—the leadership was acutely aware of both manufactured communal agitation and genuine religious concerns, seeking to distinguish between pandering to sectarian pressure and addressing legitimate grievances.

The Constituent Assembly Debates

A decade later, the question of “Vande Mataram” resurfaced as India’s Constituent Assembly worked to establish the symbols and institutions of the new republic. The debates between 1947 and 1950 revealed that the 1937 resolution had not settled the matter—if anything, independence amplified the stakes.

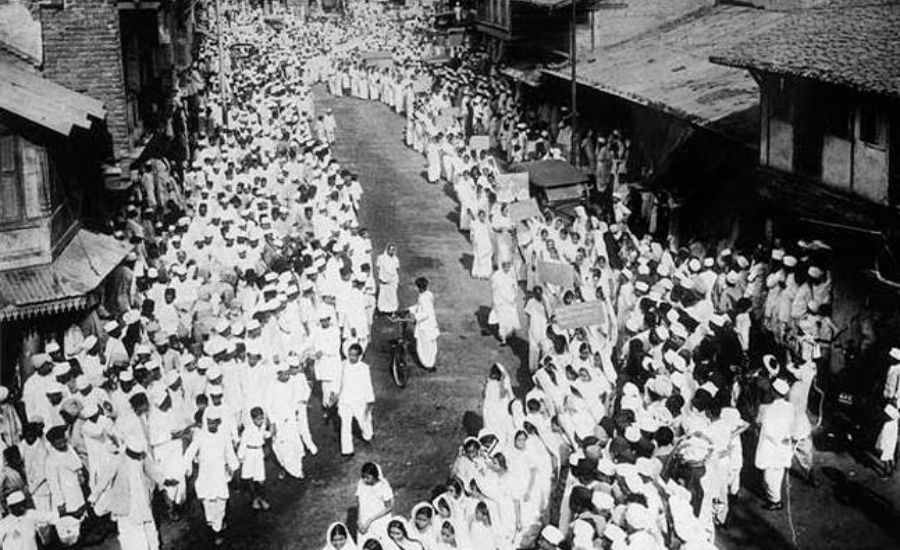

On 31 July 1947, H. V. Kamath urged the Assembly to include “Vande Mataram” in its official program alongside other patriotic songs. Two weeks later, on the historic night of 14 August 1947, Shrimati Sucheta Kripalani sang the first verse of “Vande Mataram” as the opening item of the Assumption of Power ceremony, marking the song’s inspirational role at the birth of independent India.

Yet tensions surfaced immediately. On 26 August, Kamath brought to the Assembly’s attention that several members had entered the hall only after the song had been sung on that historic night. He noted they entered “simultaneously,” suggesting the act was performed “not so much by accident as by design.” Noting the apparent disrespect, Kamath then emphasized that while “Vande Mataram” had not been formally adopted as the National Anthem, it was a song “hallowed, consecrated, sanctified by the suffering and sacrifice, blood and tears, and the martyrdom of thousands of our countrymen and women.”

The debates throughout 1948-49 revealed the depth of feeling surrounding the song. In November 1948, Seth Govind Das argued forcefully for “Vande Mataram” as the true national anthem, emphasizing its association with the freedom struggle. He contrasted it with “Jana Gana Mana,” claiming Tagore’s composition had been written on the occasion of Emperor George V’s 1911 visit to India, offering greetings “not to Mother India, but to the late King Emperor.” Das argued that in a republic, India could not have a national anthem that greeted any “Rajeshwar” (Emperor), making “Vande Mataram” the only appropriate choice.

Bengali members expressed particular pride in “Vande Mataram” and its author. Satish Chandra invoked it as the “Mantram” given by Bankim Chandra Chatterjee that inspired thousands to sacrifice for freedom. Syama Prasad Mookerjee celebrated Bengali as “the language of Vande Mataram” and praised Rabindranath Tagore for raising India’s dignity at “the bar of world opinion.” Purushottam Das Tandon traced the national language movement to 19th-century Bengal, citing writings by Bankim Chandra Chatterjee and noting that Aurobindo Ghose had edited a publication titled “Bandemataram.”

Religious dimensions also emerged in the debates. Rohini Kumar Chaudhuri, in October 1949, reminded the Assembly that India’s political movement began with “Bande Mataram”—an invocation to a Goddess. He objected to invoking God while ignoring the Goddess, arguing that those belonging to the Shakti cult deserved equal recognition. Biswanath Das expressed his preference for “Vande Mataram” over “Jana Gana Mana,” noting it had inspired the nation for fifty to sixty years, though the President indicated a committee would be formed to select the best song or even compose a new one.

On January 24, 1950, President Rajendra Prasad announced the final resolution: “Jana Gana Mana” would serve as the National Anthem, while “Vande Mataram,” having “played a historic part in the struggle for Indian freedom, shall be honoured equally with Jana Gana Mana and shall have equal status with it.” The announcement was met with applause, representing an attempt to harmonize the dual legacy of patriotism and cultural plurality embodied by both songs.

The Contemporary Debate

These historical episodes—the 1937 resolution and the Constituent Assembly debates—demonstrate that “Vande Mataram” has always existed at the intersection of reverence and controversy. The song served as a rallying cry for sacrifice and freedom while requiring sensitive handling of its religious overtones within India’s plural society.

The current parliamentary controversy reveals two persistent tensions in Indian political life. First, political parties and civil society remain engaged in competing interpretations of India’s history, each claiming authentic ownership of the nationalist legacy. The ruling party’s accusation that the opposition removed portions of the song, and the opposition’s defense citing their party’s own historical decisions, shows how “Vande Mataram” continues to serve as a battleground for defining the nation’s past and present.

Second, the controversy exposes a fundamental disagreement about how a republic should address diversity. When the Indian National Congress restricted the song to its first two stanzas in 1937, leaders like Nehru understood this as an exercise in principled nation-building—distinguishing between manufactured communal agitation and genuine grievances, making accommodations to ensure all communities felt represented in national symbols. Others view this same action as evidence of appeasement, arguing that it established a problematic precedent of yielding to sectarian demands rather than forging a common national identity that transcended such concerns.

The intensity of the recent parliamentary debate suggests that the compromises forged in 1937 and 1950, far from settling the matter, created a framework that each generation must navigate anew. The question is not merely about a song, but about how the Indian republic negotiates its symbols, its memories and origins.