On 14 September 1949, Hindi was accepted as the official language by the Constituent Assembly, which is celebrated as Hindi Diwas every year. Every year this date is also typically accompanied with statements by Hindi supporters, that predictably prompt vigorous responses from political leaders and regional language activists from non-Hindi speaking regions. These exchanges are foreshadowed by earlier debates on the national language in the Constituent Assembly which deserve closer attention.

The ”Hindi-wallahs” (as Granville Austin referred to them) in the Assembly included those who proposed to make Hindi India’s sole national language, to replace English as the official language for governmental communication, and to be promoted as a second language in non-Hindi speaking states. They also preferred a Sanskritised version of Hindi, divested of the diverse cultural influences that had influenced its development. Many other members, from both Hindi-speaking and non-Hindi-speaking regions, were not satisfied with this proposal. Shankar Rao Deo, a Gandhian, said:

“They appeal to us in the name of unity, in the name of culture, that this country must have one language. They say unless this country has one language, there cannot be unity and one culture; and if there is no unity and one culture, then, this country has no future. in the same breath we are told that the regional languages must be enriched… I cannot understand how these two things can go together. I think we are speaking with two minds. We cannot hope to have one language for the whole country and at the same time work for the enrichment of the regional languages and assert that they must be maintained, and they must have a permanent place in the national structure or life. I have tried my best to understand how these two things can go together but failed…”

Hindi antagonists responded that if the primary function of a national language is to unite India, then English was a workable choice. Firstly, different regions of India might be more inclined to adopt neutral English rather than Hindi as a link language for official communication. Secondly, English had already unified different parts of India and facilitated communication, although only among a certain class of multilingual Indians. Maulana Abul Kalam Azad observed that English had become essential to the Indian Union in civilizational terms:

“We have got to admit that so far as language is concerned North and South are two different parts. The union of North and South has been made possible only through the medium of English. If today we give up English then this linguistic relationship will cease to exist.”

However, English was also seen as a colonial and ‘foreign’ language. As a result, various members were anxious about making English the national language. Faced with the existential consequences of a hasty adoption of a national language, the founders avoided declaring a national language at all. Instead, they used the more ambiguous term ‘official language’.

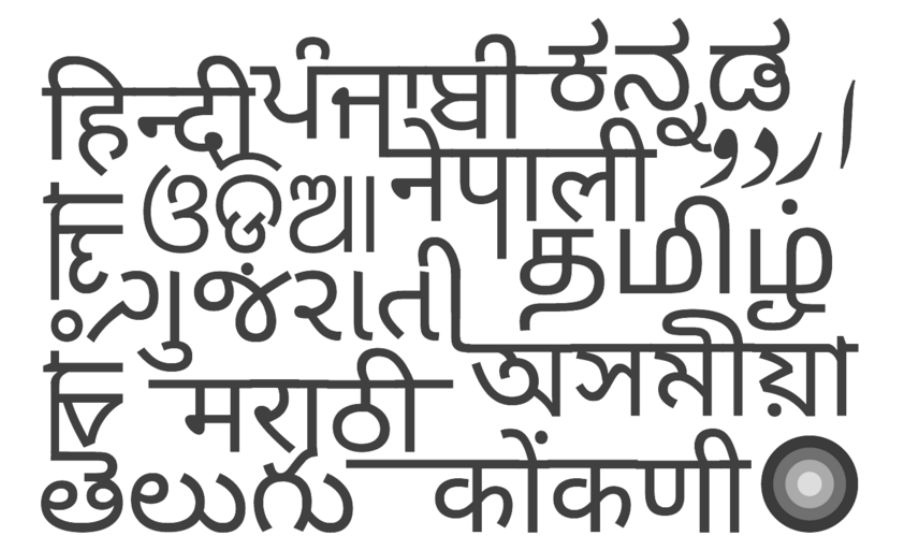

Under the ‘Munshi-Ayyangar’ formula, Hindi in the Devanagari script was declared as an ‘official language’ for the Union government, along with English. Also, 13 other languages were included in the 8th Schedule (now expanded to 22) as ‘official languages’, from which elements may be drawn for the enrichment of Hindi. In this way, the Assembly tried to de-link language from nationalism and national identity, and to an extent succeeded in placating all parties to the debate.