By August 1947, the Indian Constituent Assembly had been nine months into drafting India’s Constitution. Initial drafts of key provisions prepared by the Assembly’s Committees were presented for debate in the plenary Assembly. On 30 August 1947, during a debate around an early draft of the Directive Principles of State Policy, P.S. Deshmukh launched the following attack:

‘…Our problems are huge, our population is big and we cannot merely sit and take portions from here and from there and especially from an Irish constitution. After all, what is this Constitution? We have parts of the Irish Constitution copied out and we have three-fourths of the Government of India Act of 1935 copied out…’

Given that this statement was made a mere fifteen days after India gained independence, Deshmukh’s accusation of thoughtless adoption of Ireland’s constitutional provisions and the notorious British imperial legislation might have been received by some with a mixture of irony and apprehension. In fact, a month earlier, B. Das, in an impassioned intervention, told the Assembly that he was ‘sick of hearing…that in certain respects we are following the Government of India Act’ and that he was ‘ashamed’ and ‘humiliated’.

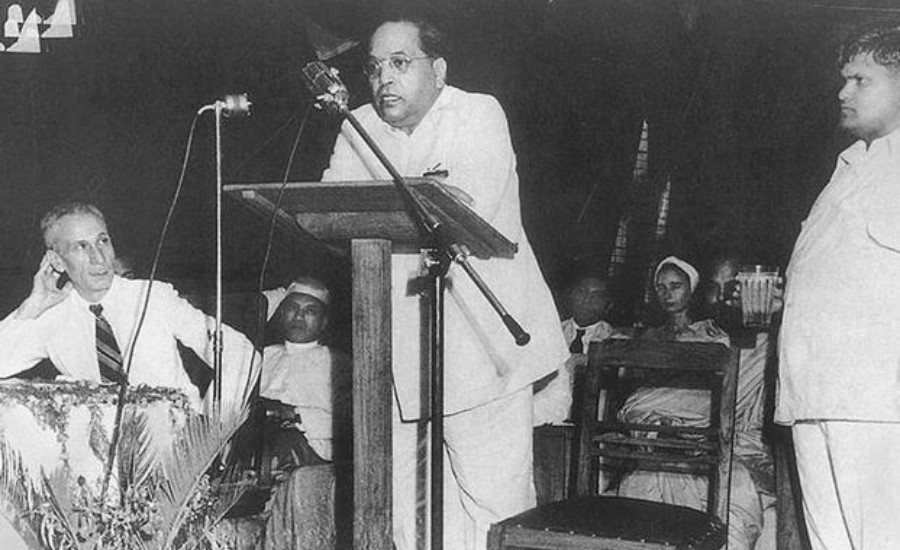

As constitution-making chugged along, and the plenary Assembly was served with more and more provisions for its consideration, comments on the borrowed nature of various provisions continued to punctuate the proceedings. This peaked in November 1948 when Dr BR Ambedkar presented the Draft Constitution 1948 – the first consolidated draft of the Constitution of India 1950.

The document had been submitted to the President of the Constituent Assembly in February 1948 and had been in public circulation since then. Now, Ambedkar was formally presenting the document to the larger plenary Assembly for its consideration. He anticipated that members of the Assembly would challenge him on the issue of borrowing. He came prepared:

‘It is said that there is nothing new in the Draft Constitution, that about half of it has been copied

from the Government of India Act of 1935 and that the rest of it has been borrowed from the Constitutions of other countries. Very little of it can claim originality. One likes to ask whether there can be anything new in a Constitution framed at this hour in the history of the world. More than hundred years have rolled over when the first written Constitution was drafted. It has been followed by many countries reducing their Constitutions to writing. What the scope of a Constitution should be has long been settled. Similarly, what are the fundamentals of a Constitution are recognized all over the world. Given these facts, all Constitutions in their main provisions must look similar.’

Having acknowledged and justified borrowing, Ambedkar then proceeded to persuade members that it was unfair to view the document as entirely borrowed:

‘The only new things, if there can be any, in a Constitution framed so late in the day are the variations made to remove the faults and to accommodate it to the needs of the country. The charge of producing a blind copy of the Constitutions of other countries is based, I am sure, on an inadequate study of the Constitution. I have shown what is new in the Draft Constitution and I am sure that those who have studied other Constitutions and who are prepared to consider the matter dispassionately will agree that the Drafting Committee in performing its duty has not been guilty of such blind and slavish imitation as it is represented to be.’

In recent years, the borrowed nature of the Constitution has resurfaced in public discourse across academic and popular political forums, making grand assertions about India’s constitutional founding. One recent work even goes so far as to label India’s founding document as a Colonial Constitution. What’s striking in these debates is the complete absence of quantitative rigor in substantiating these claims. A quantitative analysis of foreign borrowing in the Constitution would allow us to accurately assess claims made in the Constituent Assembly and contemporary debates. This is precisely the objective of one of the academic papers that the PACT team will produce this year, employing tools from natural language processing to analyze the Constitution of India 1950.