In an earlier post commemorating International Workers’ Day, we examined the provisions relating to workers’ rights in M.N. Roy’s Constitution of Free India: A Draft (1944). We now turn to the 1948 Draft Constitution of Indian Republic published by the Socialist Party [hereinafter Draft Constitution (Socialist Party)], to explore its approach to workers’ substantive rights.

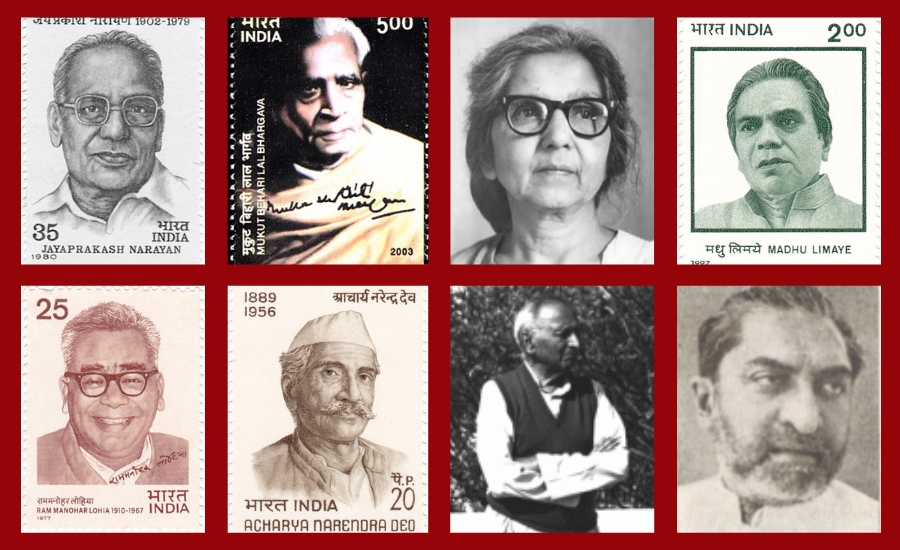

The Socialist Party originated as a political party within another: its members included leaders of the Indian National Congress who differed from other party leaders on the desirable extent and mechanisms of socio-economic redistribution. These ideological differences were manifested in the framing of the Draft Constitution (Socialist Party), which was published after the Assembly’s Drafting Committee had prepared the Draft Constitution of India 1948. The Draft Constitution (Socialist Party) was meant to assert an alternative imagination of independent India’s “fundamental law”, given that “The Indian Constitution is not likely to be, unless drastically amended, a fit instrument of full political and social democracy.”[1] While this constitutional document shares significant commonalities with the Constitution of India, 1950 [hereinafter Constitution of India], its provisions also differed from the latter in significant ways. This is true of the constitutional documents’ visions of workers’ rights.

In this post, we compare and contrast the Draft Constitution (Socialist Party) and the Constitution of India across two common themes. These are first, the types and scope of workers’ rights that they recognise; and second, the extent to which these rights are judicially enforceable.

There is a notable degree of overlap between the Constitution of India and the Draft Constitution (Socialist Party) in terms of the substantive rights they accord to workers. In the civil-political sphere, both documents recognise the rights of citizens to assemble peacefully and to form associations or unions—[2] rights that serve as crucial foundations for collective worker mobilisation. Both also prohibit forced labour[3] and the engagement of children under 14 years in hazardous work.[4] Furthermore, each constitution guarantees equality of opportunity in public employment, and bars discrimination based on the specified identity markers.[5] These provisions can support demands for affirmative action to improve access to public employment for individuals from marginalised communities.[6]

In the realm of socio-economic rights, both constitutions place obligations on the State to safeguard and advance citizens’ interests in relation to work, both within and beyond the workplace. These obligations include securing adequate means of livelihood,[7] ensuring “just and humane” working conditions,[8] providing for maternity relief,[9] and ensuring sufficient employment opportunities.[10] In addition, both documents direct the State to protect the health and strength of workers against exploitation.[11]

Despite these commonalities, the Draft Constitution (Socialist Party) articulates a broader and more detailed vision of workers’ rights than the Constitution of India. It offers a range of specific protections governing the rights of workers and their relationship with employers—protections that are largely absent in the Constitution of India.

For example, the Draft Constitution (Socialist Party) explicitly confers on “peasants and workers” the right to form various types of organisations and associations, rights that cannot be contractually waived or curtailed.[12] It also subjects employers’ “freedom of negotiation and organisation in business affairs” to laws made in the “social interests,”[13] and mandates State support for the establishment of educational institutions for workers.[14] These provisions are particularly significant for redressing the imbalance of bargaining power between workers and employers, especially in sectors characterised by informal or precarious employment arrangements. Notably, the Draft Constitution (Socialist Party) envisages a direct legal relationship between the State and “tillers of the soil,” and enables legislation to confer land title upon them.[15]

Such legal specificity enhances the prospects for meaningful judicial interpretation and enforcement of workers’ rights. In contrast, the Constitution of India articulates workers’ rights in more general terms, without the same degree of clarity.

The articulation of constitutional rights is the first step in protecting workers’ interests. The second step is to provide constitutional mechanisms through which the State may be held accountable towards respecting or protecting these rights. On this count, the Draft Constitution (Socialist Party) differs interestingly in its approach to the realisation of workers’ socio-economic rights. This is because under the Constitution of India, the specific provisions relating to workers’ socio-economic rights fall primarily under the Part IV of the Constitution, titled the ‘Directive Principles of State Policy’.[16] The provisions in Part IV are “…not…enforceable by any court…”, even as the State is bound to apply the ‘principles’ posited in this Part while making laws.[17] This indicates that under the constitutional text, the State was intended to be held accountable for enforcing workers’ socio-economic rights through mechanisms other than the kind of judicial enforcement which has been enabled for workers’ civil-political rights under Part III,[18] before the Supreme Court and the High Courts.[19]

In contrast to the Constitution of India, under the Draft Constitution (Socialist Party), the socio-economic rights of workers have been spread out across the chapters titled the ‘Justiciable Fundamental Rights’ and the ‘Directive Principles of the State Policy’.[20] Further, the Draft Constitution empowers the judiciary to enforce the “fundamental rights and other provisions of the Constitution”.[21]

Conclusion

The Draft Constitution (Socialist Party) envisions a more expansive and concrete framework for workers’ substantive rights than the Constitution of India. Further, the Draft Constitution (Socialist Party) differs in its approach to the appropriate mechanisms for the enforcement of some of these rights. This constitutional vision provides insights into how different political actors of the time conceptualised workers’ rights. Further, it offers valuable perspectives for rethinking and strengthening the protection of workers’ rights in contemporary India, particularly in contexts marked by economic vulnerability and precarity.

[1] Draft Constitution (Socialist Party), Foreword by shri Jayaprakash Narayan.

[2] Constitution of India, Article 19; Draft Constitution (Socialist Party), Article 25.

[3] Constitution of India, Article 23; Draft Constitution (Socialist Party), Article 27.

[4] Constitution of India, Article 24; Draft Constitution (Socialist Party), Article 47.

[5] Constitution of India, Article 16; Draft Constitution (Socialist Party), Article 20.

[6] For enabling provisions to this effect, see Constitution of India, Article 16; Draft Constitution (Socialist Party), Article 23.

[7] Constitution of India, Article 39; Draft Constitution (Socialist Party), Article 57.

[8] Constitution of India, Article 42; Draft Constitution (Socialist Party), Article 56,

[9] Constitution of India, Article 42; Draft Constitution (Socialist Party), Article 56.

[10] Constitution of India, Article 41; Draft Constitution (Socialist Party), Article 56.

[11] Constitution of India, Article 39; Draft Constitution (Socialist Party), Article 56.

[12] Draft Constitution (Socialist Party), Article 44.

[13] Draft Constitution (Socialist Party), Article 45.

[14] Draft Constitution (Socialist Party), Article 41.

[15] Draft Constitution (Socialist Party), Article 43.

[16] Constitution of India, Part IV.

[17] Constitution of India, Article 37.

[18] Constitution of India, Part III.

[19] Constitution of India, Article 32 (for the Supreme Court), 226 (for the High Courts).

[20] Draft Constitution (Socialist Party), Chapters III and IV.

[21] Draft Constitution (Socialist Party), Articles 53, 217, 224.