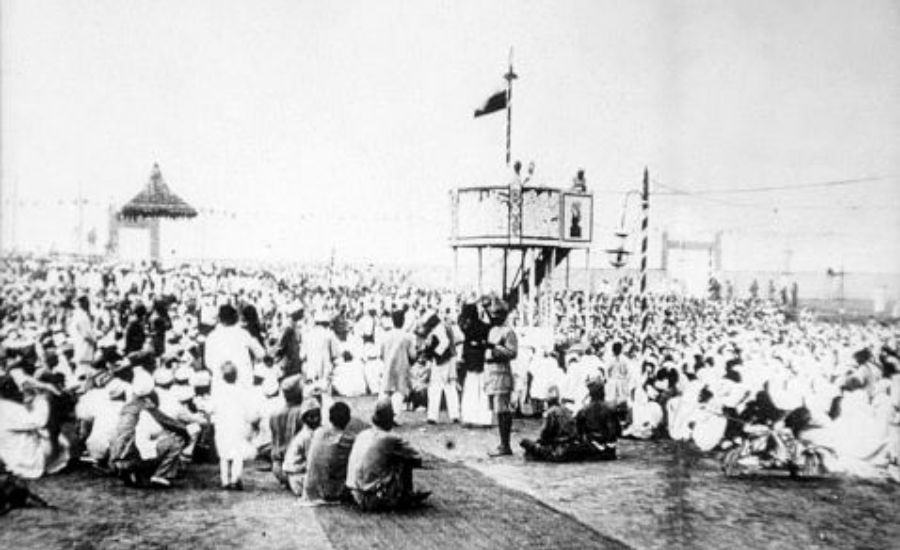

In March 1931 thousands of Indians from across the country gathered at the Port city of Karachi. Among them were the leaders of India’s freedom movement, including Jawahar Lal Nehru, Sardar Patel, and Sarojini Naidu who were promptly garlanded and cheered on by a sea of Indians. The atmosphere was festive and energetic.

The Indian National Congress (INC) convened for its 45th session. These sessions were an annual event bringing together the Congress party’s rank and file to take stock of recent political developments and chart out the party’s activities for the next year and beyond. They were usually marked by pomp and fervor. But there was something different at the Karachi session. The mood was not all celebratory. Some sections of the crowd were restless and on the edge. But why?

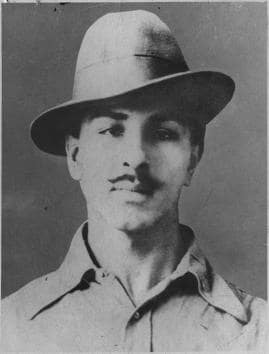

The Karachi Session was held under the background of seismic political events. To the shock of the Indians, the British executed the revolutionary Bhagat Singh and his associates for their role in the Lahore conspiracy case. This was just a week before the Karachi session. Gandhi had just agreed to a pact with British Viceroy Lord Erwin and suspended the Civil Disobedience Movement in return for political concessions. These developments had angered the more radical and socialist-leaning members of the Congress party and their supporters. The atmosphere at Karachi before the Congress session began was a cocktail of anger, hope, discontent, and excitement.

After all the Congress party leaders arrived, they got to work. They discussed recent political developments and how Congress should respond. At the end of the session, they passed a Resolution on ‘Fundamental Rights and Economic and Social Change’, commonly referred to as the ‘Karachi Resolution’. The Resolution was a three-page document, written in a quasi-legal style. It reiterated the Congress party’s commitment to obtaining ‘Poorna Swaraj’ or complete independence for India. It declared a bouquet of civil rights for Indians, that included free speech, equality, and religious freedom. What made the Resolution stand out and raise eyebrows was its declaration of socio-economic rights for Indians.

The inclusion of such rights was not completely new. The Nehru Report had done so in 1928. However, the Karachi Resolution was different, in that it placed socio-economic rights as central to India’s constitutional and political goals. Also, these rights had a distinct socialist slant. The Resolution declared that ‘To end the exploitation of the masses, political freedom must include the real economic freedom of the starving millions‘. It provided constitutional protection for industrial and agricultural workers and declared that the state must own or control key industries and services.

The Resolution’s strong socialist provisions have been the subject of scholarly attention. Who was behind the socialist provisions in the Resolution? And how did the Congress leadership agree to include these socialist provisions? Professor Kama Maclean in ‘A Revolutionary History of Interwar India’ argues that there is evidence to suggest that the political activist and revolutionary M.N. Roy was behind the socialist provisions. Incidentally, it was M.N. Roy who first mooted the idea of an Indian Constituent Assembly. We also learn from Professor Kama Maclean that the Congress adopted the socialist-heavy Resolution to mollify Nehru and the other left-leaning Congress members in the wake of Bhagat Singh’s execution and to also obtain their support for the Gandhi-Irwin Pact.

The Karachi Resolution marked a turning point in how Indian political actors viewed the constitutional future of India. The Resolution declared, loud and clear, that a future Constitution of India could not simply provide for civil rights and remain silent on the socio-economic conditions of Indians.

More blog posts

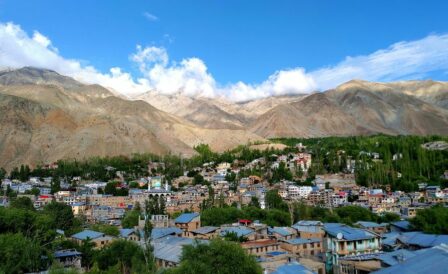

Ladakh’s Sixth Schedule Demand

25 February 2023 • By Varsha Nair

Ladakh has been witnessing huge protests demanding constitutional safeguards for the region under the Sixth Schedule. We examine if this demand is legitimate.