In 1934 the State of Louisiana introduced a law that imposed a tax on the income of newspapers with a circulation greater than 20,000 copies per week. Newspapers alleged that the U.S. Democratic Party Senator and former Louisiana Governor Huey P. Long, who enjoyed immense political influence in the State, was behind this law. They claimed that the law was intended to punish the students at Louisiana State University who had published editorials critical of Long’s politics in their student newspaper.

The U.S. Supreme Court in Grosjean v. American Press Co. (1936) agreed. It struck down the law because it violated the freedom of press. The Court noted that while newspapers should not be exempted from ordinary taxation, the tax in this case, was ‘a deliberate and calculated device in the guise of a tax to limit the circulation of information to which the public is entitled in virtue of the constitutional guarantees’.

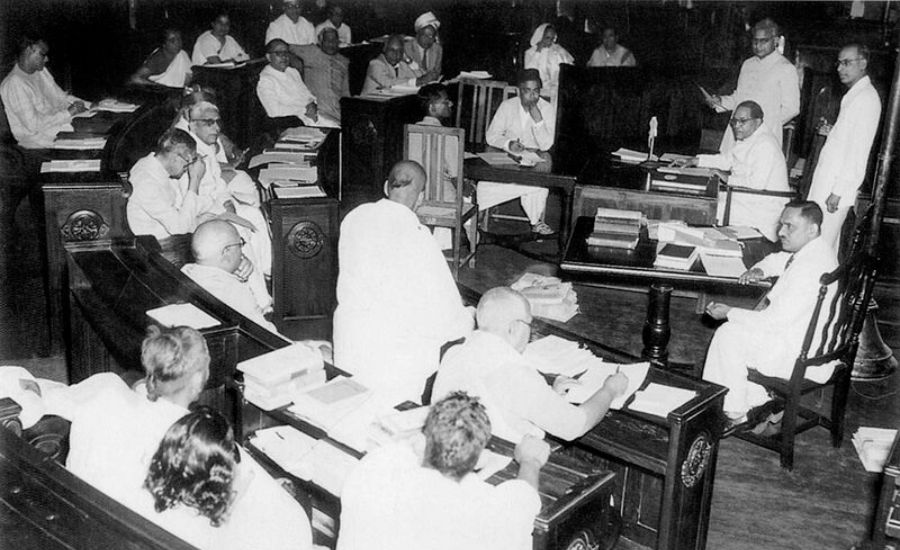

Fifteen years later, this case would make its way into the Indian Constituent Assembly. On 1 October 1949, Constituent Assembly members had taken up the Draft Constitution’s Seventh Schedule for debate. This provision distributed legislative powers between the Union and State legislatures. The power to tax newspapers was placed under the State Legislature’s control. Ramnath Goenka, who founded the Indian Express in 1932, proposed that this power be shifted to the Union. Responding to Goenka’s proposal, Deshbandu Gupta steered the discussion in the Assembly onto a more fundamental question: Does the taxation of newspapers violate freedom of speech and press?

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Gupta argued it did and passionately brandished the judgment in Grosjean v. American Press Co. to back him up. He read out excerpts from the judgement and told the Assembly that a tax on newspapers violated the Draft Constitution’s freedom of speech provision. He further pointed to the role of the Press in the freedom movement and argued that it was vital for the existence of a democracy.

In what might have been a pre-planned move, Jagat Narain Lal and Naziruddin Ahmad also stood up and read out from the same judgement. Narain referred to the judgment’s invocation of U.S. history—American colonies first resisted the British in 1765 when the British Government imposed duties on newspapers as a means to curtail criticisms against the government. Ahmad argued that even if the legislature had no ill intent, a tax on newspapers could mean curtailing circulation of newspapers and consequently lead to a suppression of opinion.

The Assembly President asked B.R. Ambedkar to respond to these interventions. Ambedkar said that to judge if a particular tax on newspapers violated freedom of speech or freedom of press, one had to ask—what was the nature and severity of the tax? From his reading, Grosjean did not ask these questions and therefore its invocation by Gupta and others was irrelevant.

Image Credits: The Print

Ambedkar, it appeared, had one of his own U.S. Judgments to refer to. He quoted from Gitlow v. New York, and stated that it was an acknowledged position in the U.S. that constitutional freedoms like freedom of press and speech were not absolute. Further, he clarified that unless a tax is so oppressive that it strikes at the foundations of a right, it couldn’t be held as invalid. Alladi Krishnaswamy Ayyar, a Drafting Committee Member added that the Courts could always intervene if the Legislature was in any way going beyond its authority and posing a threat to the freedom of press. Both Ambedkar and Ayyar, suggested that the Court should decide if a particular tax passed by a State or Union legislature infringed freedom of press.

The Assembly seemed to agree. Deshbandu’s passionate use of U.S. case law did not convince the Assembly to let go of the taxation of newspapers. This debate in the Constituent Assembly reveals how there was careful deliberation on not just provisions of foreign constitutions, but also case law. These were an important resource for Constitution framers in advancing their argument in the Assembly. Further, this shows, contrary to the opinion of many writers, that the Indian Constitution framers did not blindly ‘copy’ or get influenced by the foreign constitutional provisions and experience. In many instances, like the one around newspaper taxation, they rejected foreign constitutional law.